As part of our #SmartHealthSystems study which examines the digital transformation of health care systems in 17 countries, we’ve visited five of these countries to take a closer look at what they’ve achieved. In each country, we’ve inquired about the political, cultural, technological and economic factors driving success as well the obstacles to a successful digitization strategy in healthcare. We will publish the findings of our cross-national study in full in November 2018. Until then, we’ll be highlighting thought-provoking insights and best practices from other countries here in our blog. During our visit to France, we found that although the introduction of an electronic health record system can involve a long and difficult struggle, it can succeed if the proper institutions are in place to ensure coordinated implementation. Doctors and patients, however, need to be convinced of the usefulness of EHRs.

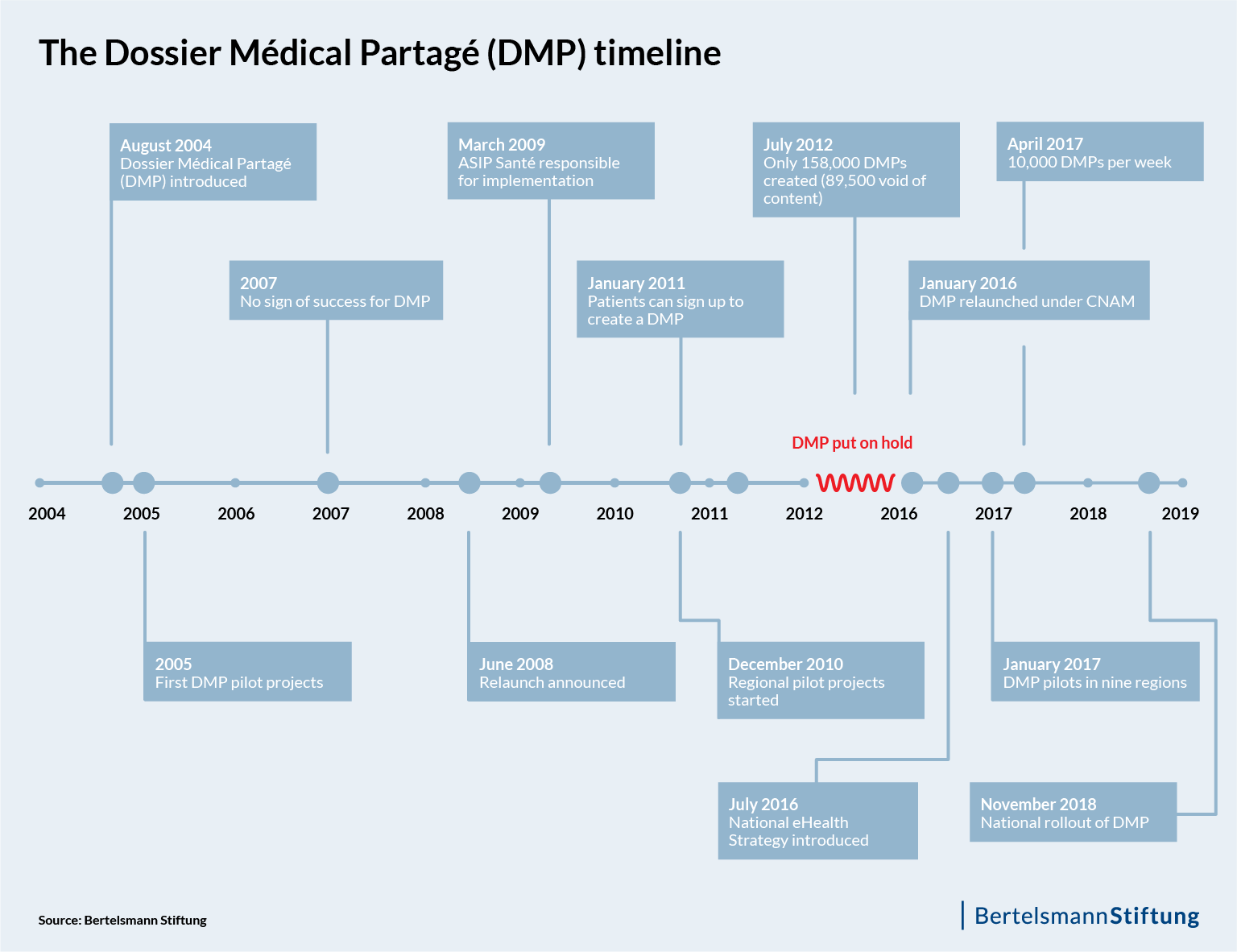

Imagine a scenario in which an electronic health record system is in place, but nobody uses it. This is in fact what happened in France in 2004, when the French Ministry for Solidarity and Health officially launched its Dossier Médical Personel (DMP). Law number 2004-810 was intended to ensure that every insured resident had a digital file with all their medical data that could be accessed at any time and from any location.

But the promise of electronic records fell at first on deaf ears. In the initial pilot projects, the idea found little acceptance among the population, and even medical staff in clinics, for example, made little use of it because of the frequent problems with data transfers and the fact that files could not be integrated everywhere into existing systems in hospitals.

In the years following, it became apparent that these problems constituted more than the usual growing pains of a new product on the market. In April of 2018, an article in “Le Figaro” pointed out that: Despite the half a billion euros spent since the launch of the DMP in 2004, the Médical Partagé dossier, as the patient file is now officially called, has “thus far proven to be a fiasco.”

But this could soon change. Recently, headlines like the following are increasingly seen in the media: “What you need to know now about the Médical Partagé dossier.” “This is how the Médical Partagé dossier works.” The reason for this kind of service-oriented reporting is the recent health ministry announcement that the DMP will be accessible to all French residents with social security status by November 2018.

After a long delay and more than a decade of efforts, the DMP now appears ready for widespread use across the country. But before it could reach this point, France’s electronic health record stumbled several times along the way.

At first failure, a pause, then a relaunch – and a again a failure

In the first few years after launching the DMP, many attempts were made to resolve the DMP’s compatibility issues with existing information systems. In fact, regional pilots of a new version of the DMP were repeatedly launched – but without success. Stalled in its tracks, the DMP made no headway until 2008 when then-Minister of Solidarity and Health Roselyne Bachelot decided to relaunch the project. But even the relaunch failed. Neither physicians nor citizens really warmed up to the idea of an electronic health record. Already eight years in, considerable sums of money had been invested into the project. According to the French Court of Audit, the government had already invested nearly a half a billion euros into some 158,000 dossiers, of which 89,500 were empty of content.

As a result, the government decided in 2012 to put the idea of an electronic health record on hold, at least for the moment. This “moment” lasted four years – until 2016. This was the year in which the second generation of the DMP was introduced as part of the government’s new eHealth strategy “Stratégie nationale e-santé 2020,” which was designed to help guide health sector stakeholders through the changes associated with digital transformation and foresaw nearly €2 billion in investment. As a result, in 2017, nine regions (départements) were selected for testing the introduction of electronic health records in the pilot phase.

2018 – “The DMP is finally ready to be used”

Today, several changes of government later, Health Minister Agnès Buzyn is optimistic that this system will be the right one. “The DMP is finally ready to be used,” she stated at the start of 2018. More than othoune million dossiers have been filed in the nine pilot regions.

Although the French government has already tried several times to rollout the electronic health record nationally – leading the media to refer to the project as an “old hobby horse” – unlike Germany, France now has an electronic health record system that will be available to every French resident as of November.

In contrast to its earlier versions, the new DMP allows not only physicians but patients as well the opportunity to start a dossier. Patients can thus determine themselves which documents and data a physician can view. In addition, patients can have documents with incorrect information removed from their file and deny, if appropriate and for good reasons, certain physicians access to the DMP. Physicians can also start a DMP – but only with the patient’s consent.

In addition to personal contact information, the DMP contains information on the patient’s allergies, blood group, vaccinations, diseases, findings and diagnostic results and current treatment, as well as information on organ donation(s). Lab results, data from imaging exams and operation reports can also be saved in the DMP. In order to ensure the exchange of data between different health platforms, providers of different digital health solutions must comply with prescribed standards of interoperability.

Patients and physicians can enter information into the file

Both patients and physicians can enter information into the DMP. However, a patient’s records saved locally at a hospital are not synchronized automatically with those saved at his or her physician’s practice. It’s therefore unclear whether general practitioners in particular will use the DNP, given the considerable time investment they already have in managing their own digital or analogue health records.

A central strategy for lowering barriers to creating an electronic health record and boosting its use involves having health insurance funds voluntarily commit to providing the new DMPs automatically with a patient’s past two years of information that is based on reimbursement data. In addition, the project includes financial support for physicians if they update the software used in their practice for DMP-compatibility. Pharmacists can also create a DMP file for a patient and will receive one euro per file.

Parallel to the introduction of the first DMP in 2004, the French Chamber of Pharmacists also developed an electronic file system. This “Dossier Pharmaceutique” (DP) was intended to provide a complete overview medications taken by a patient, including the type of medication, duration of prescription, dosage and all vaccinations. In contrast to the DMP, the DP’s national rollout and reach has been much more rapid and broadscale. By 2008, the DP was approved for national introduction as an opt-out system. With the “Carte vitale,” a patient can have his DP retrieved at any time from a pharmacy and has exclusive control over who may view the data. By 2016, some 30,000 pharmacies and healthcare facilities had signed up to the system and 32 million DP files had been created – with a patient satisfaction rate of 98 percent.

Institutions oversee coordinated and broadscale implementation of electronic records

If all goes as planned, the DMP will eventually be taken up across the country and become an umbrella system for data information. The National Health Insurance Fund CNAM estimates that 2.3 million DMPs could be created by the end of the year.

France has established two institutions to ensure that the DMP’s expansion is coordinated across silos and thus successful. Since 2009, the country has featured an agency tasked specifically with digital health issues. This agency, ASIP Santé, is under the Ministry for Solidarity and Health’s supervision and is financed primarily by CNAM. Adherence to standards of interoperability and security of health information systems as well as their integration into the industry’s range of digital products is a high priority for ASIP Santé.

In the past, ASIP Santé was also tasked with developing and implementing the DMP. However, as part of the DMP’s re-launch, these duties have since been assigned to CNAM, the National Health Insurance Fund. One of the main reasons for this shift in responsibilities has to do with the fact that CNAM can, in its negotiations with physicians, render DMP use compulsory via target agreements. A second institution is the Strategic Committee for Digital Health (CSNS), which was established by the French government in 2017 as an oversight body tasked with ensuring that the national eHealth strategy is implemented as a whole.

These institutions will need to continue to work hard at convincing both patients and the medical profession of the advantages of the electronic health record. They also must continue to design implementation so that the DMP becomes an effective instrument and one that lowers costs by, for example, reducing the number of duplicate examinations.

By making the DMP available to everyone in France, the first foundational cornerstone has been laid. The country’s administrative structures are also a helpful conditional factor. Perhaps, in the not-too-distant future, we can say: Imagine a scenario in which an electronic health record system is in place, and everyone uses it.

Note: This blog post was written in cooperation with Cinthia Briseño. She supports on-site research for the survey #SmartHealthSystems with her journalistic contributions to our blog.

The study is carried out by empirica Communication and Technology Research on behalf of the Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Follow us as we take a closer look at e-health developments in various countries for our study throughout the course of 2018.

We will publish the full results of our international study in November 2018. Until then, we will be highlighting thought-provoking insights and best practices from other countries here in our blog. If you are interested in keeping up-to-date with our latest analyses, we recommend that you sign up for our email newsletter: